Recently, the most highly regarded paper in Switzerland, the Neue Zürcher Zeitung, has published an article entitled "Die Verschriftlichung der Sprache" (literally: the textualization of the language). The author observes how Swiss German is experiencing a revival in written form, thanks in part to modern communication via SMS, tweets and Facebook wall posts. Such a trend would have seemed unthinkable just twenty years ago.

Below is a translation of the article for those of you who do not know German. And I would like to pose the following questions:

- Do you consider Swiss German its own language or just a German dialect?

- Does the pervasiveness of Swiss German in Switzerland hinder (your) integration?

The Textualization of Swiss German

On Facebook, there is a page called "Schwiizerdütsch" that has more than 270'000 fans. Similar sites for the "German language" have managed to get some 85'000 fans and even the international "English Language" community on Facebook is smaller. On the Schwiizerdütsch page, like in every social network, users exchange their thoughts and opinions about everything with a preference for traditional Swiss topics, and a great deal about dialect words. For instance, someone asks about the meaning of pfägsä.

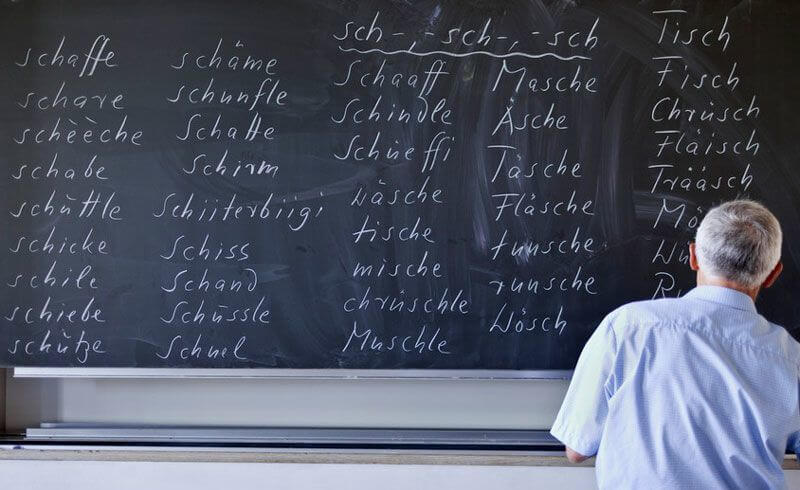

There are initiatives to collect expressions in dialect, like for example dialect words for Pfütze (puddle)*: Glungge, Guntä, Glonge, Gudlä, Gumpi, Guddha. For this word alone, there are 1400 comments. However, this page is not just interesting from a dialect dictionary point of view. It is also a testament for the explicit interest many Swiss show towards their dialect. The page provides a glimpse of the exciting development that Swiss German is experiencing today. In many ways, these developments have surpassed the existing, academic and linguistic knowledge about Swiss dialects.

The New Mobile Phone Generation

This fact is a result of a new writing phenomenon which is directly correlated to the development and spread of electronic media. In comparison to just twenty years ago, today's mobile phone, smartphone and computer owners write more often and differently than they used to.

In most languages, this is having some sort of effect. In Switzerland, the result of this trend is that Swiss dialect is becoming textualized. A parallel, written language has thus developed amongst part of the population, particularly children and adolescents. When communicating in written form, be it in a text message, a chat, an e-mail or even a postcard, young Swiss people communicate almost exclusively in dialect.

The reasons are multifaceted: Written dialect follows the tendency of informality, it serves well in the new “dialogue” form of written communication, it seems to be less serious, easier, more spontaneous and more authentic. There are no class barriers here.

"What we have had in our spoken language is now being mirrored in the written language of children," claims Dr. Helen Christen, a professor of German philology at the Universität Freiburg im. Üechtland. "Private correspondence is done in dialect and that which is meant for the public in High German. Young people are already growing up with two types of writing." This has never existed before, and at this moment the first generation of people who know no different are becoming adults. Interestingly enough, the wide array of expressions and the lack of rules for writing do not seem to cause them any problems. The first characteristics of a tendency towards a unified language can already be seen: "Within certain groups, conventions and styles are already starting to develop." Some of them like "sh" in place of "sch", and "x" instead of "gs" has already been adopted by many groups (for example Hesh xeh? [Hast Du das gesehen?/Did you see that?]). The shorter, the easier and cheaper.

With each of these moves, dialect is encroaching into the sphere of High German. The old, clearly defined usage domains that the two noncompeting languages used to operate in are now being blurred. And this is not making life for High German any easier. For linguistic reasons alone, its status in Switzerland has never really been simple. In Switzerland, High German is missing an essential element — daily spoken communication. Because of that simple fact, many Swiss lack an emotional closeness to the standard language and keep it at arm’s length. This is not just because High German is used less (and therefore the Swiss are less well versed in it), but also because directly and spontaneously expressing oneself in everyday language is easier.

The most emotional, most private, most intimate realms of language lie firmly in the hands of dialect.

Another difficulty for High German is that Swiss kids only really start to learn it when they enter school. Just recently, popular referenda in many parts have led to the teaching of High German in Kindergartens being banned. In places where only dialect is allowed to be spoken, no one bothers to take care of the High German until school starts; a blow to the language as well as to the children. How are these children supposed to become familiar with a language that will be officially used during instruction? Maybe by watching television?

Possible Developments

The Schwiizerdütsch Facebook page drove the point home: Rettet eusi Mundartsprach! S'Schwiizerdütsch wird immer meh verlore gah, und drum isch es wichtig, dass mir eus nid eusne nördliche Nachbarländer apassed. (Rettet unsere Mundartsprache! Das Schweizerdeutsch wird immer mehr verloren gehen, und darum ist es wichtig, dass wir uns nicht unsrer nördlichen Nachbarländern anpassen./Save our dialect. Swiss German is continually being lost, and that’s why it’s important that we do not conform to our Northern neighbours.)

How will things continue with dialect and High German? How will these developments line up? The loyal cult of dialect is encountering an increased public presence of High German thanks to immigration. Who will adapt to whom? Only the future will tell. However, written dialect is being used by more and more Swiss people. How much longer will parents answer their children’s text messages written in dialect with High German? It is completely imaginable that within a short time, two written languages will exist side-by-side in Switzerland. A point in time where written dialect is not just reserved for private communication, but also obtains the status of an official language.

Similar things have happened in the history of other dialects, like in Luxembourg. In 1984, the local Luxembourgish, a group of Mosel-Frankish dialects, were made a national language. Since then, it has functioned as both an official spoken and written language - along with High German and French. Grammar rules were invented and it is even partially allowed in school instruction. State officials are obligated to respond to letters from their constituents in the language they receive them in. In the newspapers, one can find articles in French, High German and Luxembourgish. The language can even be found on Wikipedia, where one can read: "D’Schwäiz ass e Staat a Mëtteleuropa. D’Land grent am Norden un Däitschland, am Osten u Liechtenstein an Éisträich, am Süden un Italien an am Westen Frankräich."

Possibly, it is just a matter of time before we can read an article about Luxembourg in Swiss German.

*This is a weird choice of word to use as an example, and one case where the Swiss German might save many German learners a great deal of embarrassment, should they falsely pronounce or intonate the High German word.

(Pictures copyright by Keystone)

Cool article.

Swiss German make my life difficult but I think formalizing it will be good for everyone. It will be easier to learn. And, It will provide a clearer swiss linguistic identity. I can’t stand it when people lift their nose at Swiss German and disrespect it.

As a Swiss growing up and living in the US, Schwiizerdütsch was my home language (just as I always understood it to be for my cousins living in Switzerland). Sure, as we vacationed and interacted with Germans and Austrians I learned the German word for my Swiss words, but it was very limited, until I took German in college. Now with Facebook etc. communication between my cousins and Swiss friends is mainly in “Swinglish”.

Sali Liesel,

Thank you for sharing your personal story! It appears that you have found a perfect way of communicating…

Dimitri

Thanks for this article. It puts into words what many of us bilingual kids grew up with in the German speaking part of Switzerland. When ask what is your mother tongue, I answer: English and Swiss German. A concept that is hard to explain, if you haven’t experienced it first hand. Next time I’ll just refer to your post. ;)

Thanks for the head’s-up! Merci villmal!