Switzerland certainly boasts some bizarre traditions, but one of the cruelest ones has to be the Böögg Bonfire during Sechseläuten. (Cruel for the Böögg, that is.)

Every year, the various guilds from the city of Zürich give back to the community by holding the Sechseläuten parade. During this city-wide Zürich holiday, children and adults walk the streets dressed in costumes from back in the day: bakers, butchers, carpenters, or merchants.

Pictures speak a thousand words:

The Sechseläuten children's parade takes place on Sunday:

On Monday, the guild members will parade along Bahnhofstrasse:

Why is the event called Sechseläuten?

The literal translation of Sechseläuten is six o'clock ringing. In the local Swiss German dialect, it is pronounced Sächsilüüte.

The German name of this tradition is derived from Zurich's ringing of the church bells every night. During winter, they would ring in the evening at 5 PM. But on a particular day in spring, the rining was postponed to six o'clock.

The tradition lives on to this day. At the stroke of 6 PM on Sechseläuten-Montag, the Böögg snowman is lit on the Sechseläutenplatz plaza in front of the opera house.

Insights about the history of Sechseläuten

The history of Sechseläuten dates back to the 16th century. At the time, Zürich's city council decided that due to the longer days during summer, work hours be prolonged by one hour. It remained common to get off at 5 PM during winter, but workers had to stay an extra hour during summer. The six o'clock ringing of the Grossmünster church bells was their cue to take off work.

As a consequence, Sechseläuten served as a notification for workers to start working an extra hour. Under the rule of Napoleon, the spring festival and its celebrations started to fade. So in the second half of the 19th century, the guilds of Zürich tried to revive Sechseläuten by staging ever more elaborate parades.

The people of Zürich, however, were largely absent from the parades. Instead, they had their own tradition of burning small "Böögge" characters made of straw. In places like the Münsterhof or at today's Kasernenareal, mainly young residents would burn dolls that symbolized the upper classes. For instance, in 1893, an alleged stockbroker doll was torched.

In the light of the disappearance of entire neighborhoods, the guilds decided to centralize these local bonfires. In 1902, the "Böögg" was first torched on Sechseläutenplatz. Every year, the guild associations rotate the duty of lighting the bonfire.

Until 1952, the event was timed on the first Monday after the spring equinox. Today, the Zurich spring festival takes place on the third Monday of April. The date is postponed by one week in case of a conflict with Easter Monday.

Why do they burn the Böögg snowman?

Zurich has long invented an explosive way to celebrate the end of the dark winter months. Just in time for the first signs of spring, the guilds of Zurich will torch a 3.5-meter tall snowman in the center of the city.

Symbolizing winter, the Böögg is lit up at the stroke of 6 PM. According to local belief, the quicker the snowman's head tumbles and/or explodes, the nicer the summer weather will turn out.

Once the fire settles down, a more recent tradition takes over: Zürich residents will gather on the Sechseläutenplatz to hold the year's first communal BBQ. Students and locals will gather around the died-down bonfire to barbeque sausages.

Fun fact: since 1991, the burning of the snowman has lasted an average of 14:30 minutes.

There is certainly a reason why this tradition has been going on for centuries. In 2003, for instance, the Böögg exploded after only 5:42 minutes. That summer, Europe was caught in a record heatwave!

Who builds the Böögg snowman anyway?

The making of the Böögg is one man's job, and his name is Lukas Meier. A visual merchandiser by trade, Meier has his work cut out for him. During a seven-year apprenticeship, he has learned the ropes from Heinz Wahrenberger, an icon in his own right. Wahrenberger had been in charge for five decades until Meier has taken over in 2016.

Meier knows the secrets to make the giant snowman appear the same year after year. Deviating from the official look would be an insult for many a guild member. The only leeway he has is with the symbolic item the Böögg holds in his hand; an item that should represent the guest canton.

No wonder the construction takes about seven days. Just the snowman's head alone takes an entire day to build. The entire snowman weighs 100 kg, which includes the wooden construction, the 140 explosives, and even the accessories such as the broom and pipe.

Once everything is in place, the Böögg will travel from Zurich-Oerlikon to his final resting place on Sechseläutenplatz. This ritual takes place early on Monday morning, the very day of his demise.

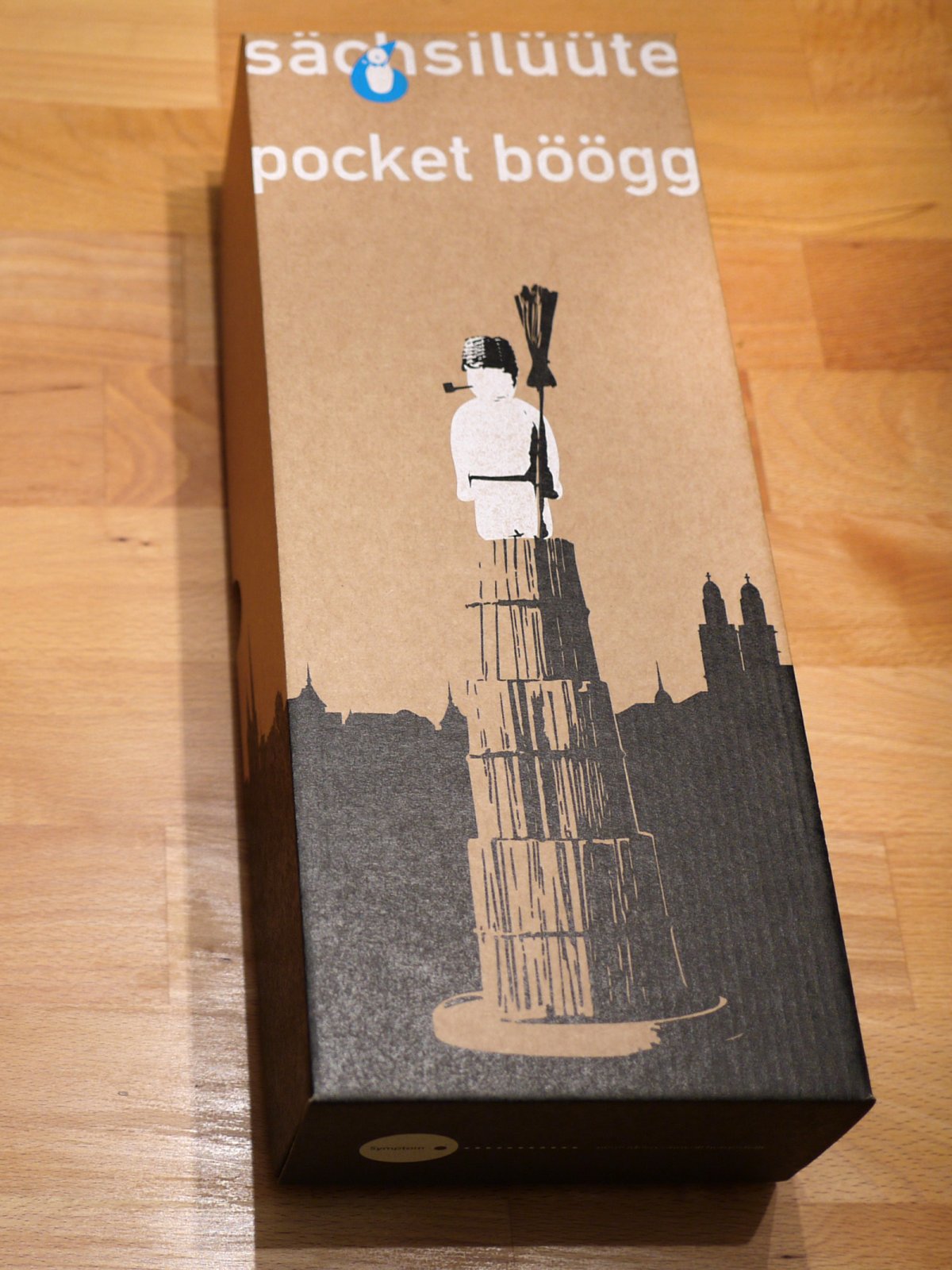

There's even a pocket-size Sechseläuten Böögg for home

When we first discovered the miniature Sechseläuten Böögg in a Zurich boutique, we could not resist it. The snowman is recreated in great detail. And there are props, too: a broom, a pipe, and a stack of wood.

The Pocket-Böögg has a social component: it was born out of a 2010 concept on how to create tasks with a meaningful for those with health conditions or impairments. Now produced at the Stiftung RgZ workshop, the Pocket Böögg has become a permanent staple in shop displays throughout Zurich. (79 francs, order information)

YES! This year we are going to have a great summer according to the Böögg. I watched it on television and it was a fantastic event in Zürich (next year in Bern). Forecast looks good and we may all expect a warm and good summer. Time was 10:56 which is a good time!

What is your plan to do in Switzerland in the summer? Don’t hesitate and leave behind a message or leave an article about summer in Switzerland!

Enjoy summer to you all!!

[…] Sechseläuten is such a simple yet spectacular event. One cannot help but wonder if one could organize a little Sechseläuten in one's own garden, the fire pit or the balcony. One can. All of us can now become summer weather experts in our own backyards – thanks to Pocket Böögg! […]

Pls visit my blog – http://www.travellers-r-us.com to read more on switzerland and europe

It’s not called Secheläuten because the bonfire is lit at six, it’s called that because the bells are rung at six (sechse = six, läuten = ringing).

[…] Knabenschiessen festival – similar to its cousin, the Sechseläuten – is an event unique to Zürich. For anyone living or working in Zürich, the two half days off […]

[…] is a quintessential tradition in Zürich that takes place every third Sunday and Monday of April. Sechseläuten quite which literally means the "six o'clock ringing of the bells", and the terms goes way back to […]

[…] and you’ll see that the Swiss aren’t so perfect after all—in fact, they’re about to burn a snowman at the stake. Writing is like that, too. It’s not just creative ideas and poetic words. It’s a […]

[…] close and personal with the Böögg… It was an awesome performance to witness the culmination of Sechseläuten from a VIP's point of view. Without knowing the right people, most "normal" people will surely have […]